What Is Technology For?

Wishes, Aliens, Immortality, and Forbidden Planet

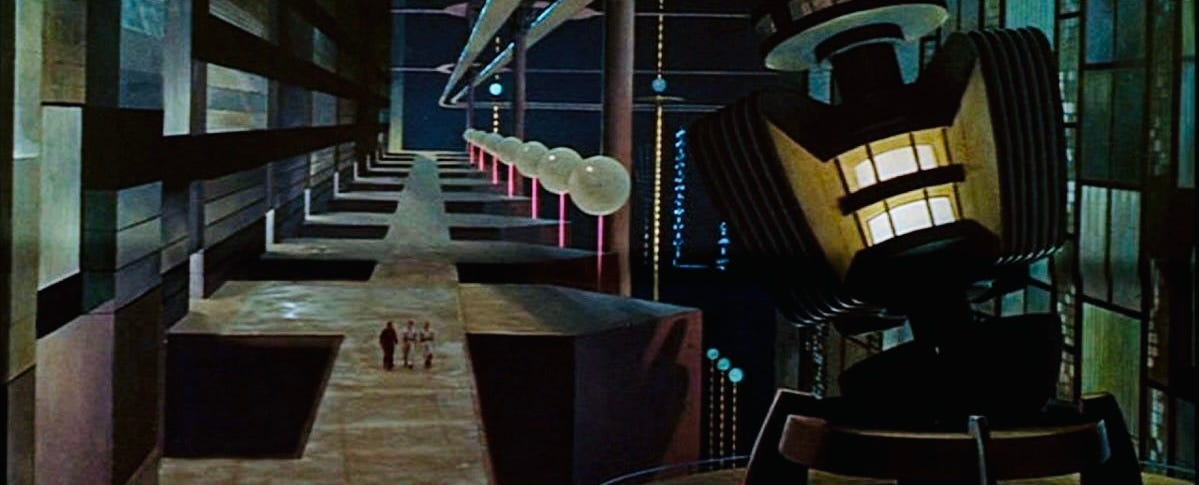

One of my favorite science fiction films is Forbidden Planet (1956), in part because it’s such a paradoxical thing—very much of its time, and at the same time very much ahead of it.

Of its time: The interstellar exploratory ship C-57D, with its US Navy-like command structure, is a trope any reader of postwar American science fiction would have immediately recognized. The shape of the spacecraft itself is borrowed from 1950s UFO lore, as if a star-traveling vehicle would necessarily be a disk with a dome on top. The only female character in the film is Altaira Morbius, raised in isolation by her scientist father and male-gazed with laser-like intensity by the starship crew. And so on.

But also ahead of its time: Some of the visual effects are strikingly modern. The planet Altair IV as seen from space could be an image from a twenty-first-century NASA probe—and it was created, not only without benefit of CGI, but a year before the launch of the first artificial satellite. Some of the matte work is obviously matte work, but it’s vivid and imaginative, and the animation of the “id monster” is only a little short of what you would expect to see today. Also unusual, circa 1956, was the idea of borrowing the plot of a science fiction movie from Shakespeare’s The Tempest. And at the heart of the story is a profound and pertinent question: Is there an end point to technological progress? Ultimately, what is technology for?

In Forbidden Planet, the vanished Krell civilization on Altair IV is portrayed as having reached that technological final destination by creating an “ultimate machine [that] would instantaneously project solid matter to any point on the planet, in any shape or color they might imagine… Creation by mere thought.” But the machine inadvertently gave the same godlike potency to the Krell’s own unconscious minds—to all their buried nightmares and long-suppressed, toxically irrational impulses. “After a million years of shining sanity,” as the character Dr. Morbius laments, “they could hardly have understood what power was destroying them.”

The sleep of reason produces monsters, and technology gives the monsters legs and teeth. It was as topical a theme in the age of atomic weapons as it is now, in the age of artificial intelligence.

Tools and Wishes

So technology is wish fulfillment, with all the ironies and caveats about granted wishes we learned from fairy tales. Is that fair?

Technology is about tools, after all, and tools often serve less than glamorous purposes. Our ancestors chipped flint so they could skin animals or hunt more efficiently. Hardly the stuff that dreams are made of. But these are also wishes: I wish I could flense this hide without using my teeth. I wish I had something more lethal than a lump of mud to throw at that rampaging mammoth.

Better and more complex technology allowed us to fulfill gaudier but equally ancient and deep-seated dreams. I wish I could cure my child’s illness, or I wish I could travel great distances with ease and safety. I wish I could fly through the air. I wish I could fly to the moon. And newer dreams: I want to see things a thousand times too small for the naked eye. I want to feel the ripples in space and time as black holes merge at the edge of the universe.

And, of courser, there are all the dreams long-dreamed but not yet fulfilled. I wish no one was poor, or I wish we could live in peace, or I wish we could cure every disease.

I wish we could travel to the stars.

I wish we could live forever.

Ghosts and Machines

There are certain malignantly wealthy Silicon Valley tech bros who claim the technological Singularity is nigh, that soon we’ll be able to merge our minds with our devices and live forever as ghosts in a digital paradise.

I would no more entrust my mortal soul to the likes of Peter Thiel or Elon Musk than I would entrust a newborn child to a herd of feral pigs, so call me skeptical. And I doubt “the mind” is something that can be pried out of the human nervous system like a walnut from a shell. This is secular theology masquerading as futurism.

Still, any physical process is said to be computable, and the mind is a physical process, so we can’t rule out the possibility of creating a digital afterlife. So is that the technological endpoint, the sum and satisfaction of all desiderata, the Krell Machine of all successful civilizations?

Maybe. But we ain’t there yet.

But maybe someone got there before us.

The Runaway Stars

The runaway stars say you shall never die at all, never at all. — Carl Sandburg, “Slabs of the Sunburnt West”

Throughout history, for any given phenomenon, naturalistic explanations have consistently displaced supernatural explanations. So if I were to die and find myself…well, somewhere else…odds are it would be the work of benevolent but not divine beings.

To be clear, I don’t expect any such thing. But I’m a science fiction writer, footloose speculation is my stock-in-trade, and we’re talking about the ultimate uses of technology, so let’s game out the possibilities—just for fun.

Premise 1: Technological civilizations have arisen in the galaxy more than once, some perhaps many millions of years before our own. [Possible, but far from a sure thing. As yet, we have no way of calculating the odds.]

Premise 2: Such civilizations often or always culminate in a digital rather than a biological existence. [Arguably plausible, even if the Krell never thought of it.]

Premise 3: Because their digital existence is portable over time and space, such civilizations—or their self-replicating von Neumann machines—could expand throughout the galaxy in a mere million years or even less. [The calculation has been done. See this Wikipedia article, which mentions my own novel Spin.]

Premise 4: They are benevolent in their intentions. [I think this is entirely plausible. Altruism, collaboration, and empathy are constructive virtues. And a digital civilization could dial these qualities up to eleven while squelching their baser impulses, unlike the hapless Krell. Curiosity rather than conquest would be enough to drive a galactic diaspora.]

Premise 5: They’re already here, though we haven’t detected them, and they are masking their presence for benevolent reasons. [We certainly haven’t detected them! The rest of this is grossly speculative.]

Premise 6: They recognize us as fellow sentient, civilization-building creatures, toward whom they have certain ethical obligations consistent with Premise 4. [Plausible, I think.]

Premise 7: Consistent with Premise 6, they are ethically obliged to offer each of us a berth in their digital afterlife rather than allowing us to die. [If possible—which is a big red blinking “if.”]

Premise 8: It’s possible for them to “rescue” our minds undetectably at the moment of death. [I can’t imagine how, and the idea raises all kinds of questions—this is entirely in the realm of “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”]

Conclusion: There is an afterlife, and aliens have built it for us.

Multiple maybes add up to one big “probably not,” so please don’t take any of this to heart. It’s all profoundly, staggeringly unlikely…but still more likely, on Bayesian grounds, than any purely metaphysical Heaven.

So if you wake up some morning with a digital body and an extraterrestrial at your bedside, don’t be surprised. And if that happens, feel free to look me up—we can find a cozy little cafe somewhere north of time and space and raise a glass to wishes granted and the ageless wisdom of the Krell.

Ethically, as well as technologically, they were a million years ahead of humankind, for in unlocking the mysteries of nature they had conquered even their baser selves, and when in the course of eons they had abolished sickness and insanity, crime and all injustice, they turned, still with high benevolence, outwards toward space. — Forbidden Planet

Re “Multiple maybes add up to one big “probably not,” so please don’t take any of this to heart.” - I’m one of those who prefer to see the glass half full rather than half empty, so to me multiple maybes add up yo one big “perhaps.”

I’ll watch again “The Forbidden Planet",” but also read again “Darwinia” with your speculations on technological resurrection. Hope is often naive, but still much better and healthier than despair. So let’s suspend disbelief in these benevolent aliens, let’s hope, and hope will give is the energy to perhaps do these things ourselves one day. Or die trying…

If my memory isn’t playing tricks on me (and it’s been a long since I read it) but some of the ideas you discussed here were part of your novel, THE HARVEST. Sadly, it seems to be out of print; at least, I can’t find it on Amazon.