Zodiac Carousel

Bell, Book and Candle and the Hinges of American Culture

Stellectric signs / “Wing shows on Starway” / “Zodiac Carrousel”

— Mina Loy, Lunar Baedeker (1923)

In my last post I mentioned the 1958 movie Bell, Book and Candle. For years it’s been my go-to Christmas movie—not a movie about Christmas in any sense, but a movie I watch at Christmas, mostly for the early scenes set in snowy late-fifties Manhattan during the Christmas season.

Maybe you’ve seen it? A lightweight romantic comedy with supernatural elements, featuring Kim Novak as Gillian Holroyd, a discontented urban witch, James Stewart as the publishing company exec she falls for, and Jack Lemmon as her ne’er-do-well warlock brother. Elsa Lanchester is Gillian’s ditzy aunt, and Ernie Kovacs, in one of his last film roles before his untimely death behind the wheel of a Chevrolet Corvair in 1962, is the inebriated author of a bestselling book called Magic in Mexico.

It’s a great cast in an enjoyable if not great film, part of a little subgenre of witches-in-modern-times stories that includes Thorne Smith’s 1941 novel The Passionate Witch and Fritz Leiber’s 1943 Conjure Wife. It’s often cited as the inspiration for the 60s sitcom Bewitched.

That’s the thumbnail description. But if you watch a movie often enough, you start to ask yourself questions. Why is this movie what it is, who did it appeal to back at the tag-end of the gray-flannel 1950s, and what does it tell us about the moment in history it inhabits?

The Lavender Scare

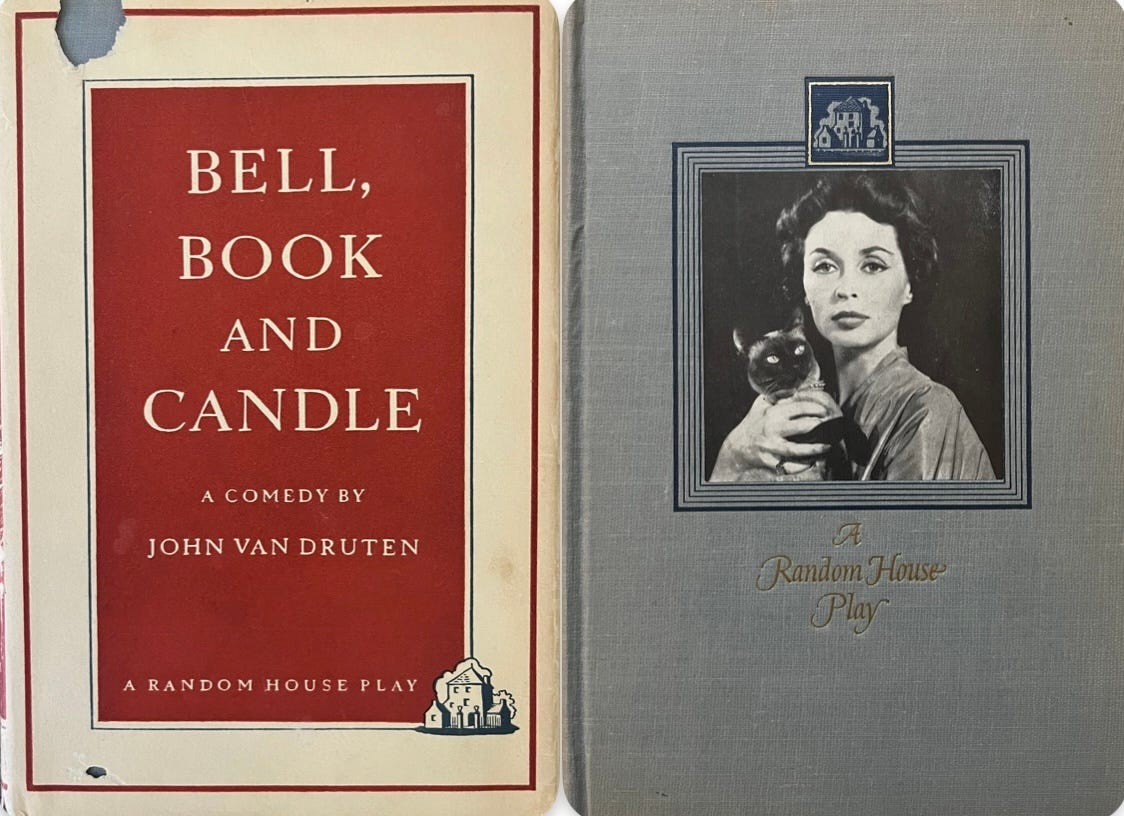

The movie is based on a 1950 stage play of the same name by John van Druten. The play had a well-received Broadway run in the 1950-51 season, with Lilli Palmer as Gillian Holroyd and Rex Harrison as Shepherd Henderson. It was successful enough that Random House published the script in a neat little hardcover edition with an inset photo of Palmer on the cloth boards: that’s the edition I have on my shelf.

Several of John van Druten’s plays had been successfully produced in London’s West End when he emigrated to the United States just before World War Two. Together with his lover Carter Lodge and the British actress Auriol Lee, he bought and lived on a ranch in California’s Coachella Valley; with his friend Christopher Isherwood—and such other mildly eccentric literary expats as Aldous Huxley and Gerald Heard—he became a member of Swami Prabhavananda’s Vedanta Society of Southern California. His next work after Bell, Book and Candle was the play I Am a Camera, based on Isherwood’s novel Goodbye to Berlin, which in turn would become the basis for the 1966 musical Cabaret.

It was a difficult time to be a gay man in van Druten’s adopted country. In 1947 the State Department began a purge of “sexual perverts” that ran parallel to Senator Joseph McCarthy’s feverishly anti-Communist Red Scare and would come to be known as the Lavender Scare. “Between 1947 and 1950,” according to Wikipedia, “over 1700 applicants to federal jobs were denied the positions due to allegations of homosexuality.” And that was only the beginning. The Lavender Scare, with its oaths of moral purity and the omnipresent threat of exposure and public shaming, intensified through the early years of the Cold War.

The government, the churches and the media were enforcing a new and deeply conservative postwar political and cultural consensus, and certain groups—the old Marxist left, outspoken progressives, bohemians, artists, intellectuals—were either written out of the social compact or viewed with suspicion. The Broadway stage could hardly have been purged of homosexuals—it would have collapsed like a burst balloon—but certain subjects were unapproachable. Playwrights like Tennessee Williams and novelists like James Baldwin (Giovanni’s Room, 1956) and Gore Vidal (The City and the Pillars, 1948) could tiptoe up to the line and even put a foot across it, but they risked their reputations by doing so.

Van Druten wasn’t doing anything nearly as daring with Bell, Book and Candle. It was intended as, and received as, a feather-light romantic comedy. But it echoed its era, as when the character Sidney Redlitch describes the subculture of urban witches:

One of their main places is up in Harlem. It’s an old vaudeville house. There’s another down in the Village. You’d be amazed what goes on under your nose that you’d never suspect. Talk about spy-rings and organized vice—they’re nothing compared to it.

Or, in one of the play’s best lines:

SHEP: What is it? Something in your past that you didn’t want questions asked about? What have you been up to? Have you been engaging in anti-American activities?

GILLIAN: No, I’d say very American. Early American!

Some in the audience would have recognized the play’s dramatic engine—Gillian’s yearning for acceptance into the “humdrum” world of her straight lover Shep—as a familiar trope about the isolation and supposed tragedy of gay life, made explicit almost twenty years later in the playwright Mart Crowley’s The Boys in the Band. But that was a different play, in a different cultural universe. In the more claustrophobic world of 1950, Bell, Book and Candle gave a knowing wink to marginalized subcultures but reassured its straight audience that, in the end, their lives were the ones worth leading.

The Return of the Repressed

The conformism of the 1950s was always fragile, which was why its borders had to be so carefully patrolled.

The cracks were there from the beginning. There were of course the familiar, mildly deviant icons of baby-boomer mythography: Elvis Presley, James Dean, Mad Magazine, et alia. But also: a public fascination with psychology and sociology that saw books like Margaret Mead’s Coming of Age in Samoa (1929) reprinted in mass-market editions; a feeling among at least some of the newly affluent middle class that their homes should be furnished with contemporary art and music; a curiosity about the European world that was growing out of the ruins of the war. In the suburbs, an ethos of cocktail-party and backyard-barbecue hedonism subverted certain venerable Protestant pieties. Out in West Hollywood, van Druten’s friend Aldous Huxley was experimenting with mescaline. And the civil rights movement, with its moral critique of American complacency, found at least a few sympathizers in the white middle class.

And there was science fiction, where a handful of talented writers were questioning the midcentury consensus from the safe space of the thirty-five-cent rotary-rack paperback.

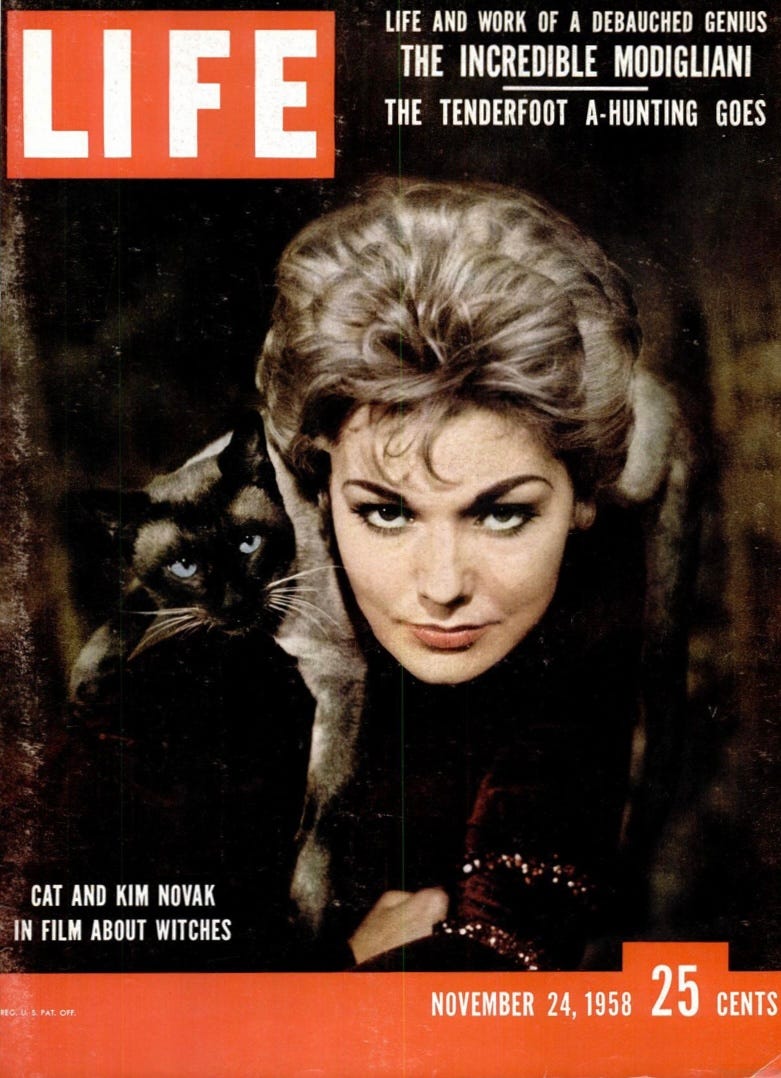

By the last years of the decade even Life Magazine, that reliable barometer of conventional wisdom, seemed to realize something was up. In 1957 it published a photo essay about the amateur mycologist Gordon Wasson’s magic mushroom experiences in Oaxaca, Mexico, anticipating the next decade’s avalanche of psychedelia. In 1959 it belatedly noticed the Beats (“Sad But Noisy Rebels”). And in 1958 its cover story was the release of the film version of Bell, Book and Candle.

Zodiac Carousel

Van Druten’s play was entirely set in Gillian Holroyd’s Manhattan apartment, but the movie expands its setting into Manhattan at large. What was only suggested in the stage play is fully visible here, for better or worse—mostly for better. (The film won an Academy Award for art direction, richly deserved.)

Gillian Holroyd, played with a pitch-perfect moody sensuality by Kim Novak, has become the proprietor of a Greenwich Village gallery specializing in African and “primitive” art, with an apartment in back. The Zodiac Club, mentioned in passing in the play, gets a lengthy scene or two. And the camera loves these spaces. The gallery/apartment is comfortable, modern, quirkily individual. The subterranean Zodiac Club, where Jack Lemmon plays bongos with a hot jazz band while beret-wearing witches and warlocks exchange catty gossip, is essentially a tourist’s idea of a Beat coffee house, sanitized for the film’s tone and audience—no politics, no drugs beyond a hint about “herbs,” and only the lightest gloss of sexual ambiguity. But, as the Elsa Lanchester character proclaims, “It’s fun!” And it looks it.

Even the witches’ supernatural powers—casting spells of summoning, picking locks, turning the streetlights dark—are mostly harmless, the cozy trickery of a low-rent underclass.

That’s all great, and beautifully visualized. But it cuts straight across the bow of the movie’s theme. If this is the witchy lifestyle, why is Gillian so anxious to leave it behind?

It’s not that Shep’s world is unattractive. He works in the publishing industry, at a time when publishing was hip and Sixth Avenue was the center of the literary world. His fiancée is an abstract artist. He’s genial and open-minded, by his own (and presumably the audience’s) standards. He has money to spend.

But by 1958 at least a part of that audience, and especially the younger part, would have found Gillian’s world more seductive. If there’s an underground club where closeted sorcerers meet, where the doorman demands to know your astrological sign before you’re admitted, where a slinky Frenchman is performing L'Assassin Ennuyé under a smoky spotlight, where the espresso flows freely and the party goes on until dawn…who wouldn’t want to be welcome there? Gillian’s disdain begins to look more like a betrayal, if not self-loathing. She admits to Shep, as if confessing a sin, that “I have always lived for and by the special. Not the ordinary.” And the audience wonders: Is there something wrong with that?

1958 was a little tired of the ordinary.

Other plot lines might have been more interesting if the script could have pursued them—how might Nicky’s collaboration with Sidney Redlitch have played out, for instance? But we’re left with the romance between Gillian and Shep, which hits all the predictable marks on its way to an inevitable and oddly disappointing conclusion.

A great cast, as I said, in an enjoyable if not great movie, but with some interesting currents running under its surface. At its best the movie signals the approach of something new—not just the decline of an artificial and oppressive conservatism but an eruption of “the special” that would turn the next American decade into a Zodiac Carousel of unprecedent proportions.

And come December I’ll watch the film again, for my own reasons—for those snowy streets, for the mystique of Manhattan at the end of the 1950s, for the gulf of time behind and ahead of us, and for the change winds blowing so incessantly outside our windows, then as now.